Pheochromocytoma Risk Assessment Tool

Risk Assessment Calculator

Enter your current measurements to assess your pheochromocytoma risk level and recommended next steps.

Results

Continue current monitoring plan

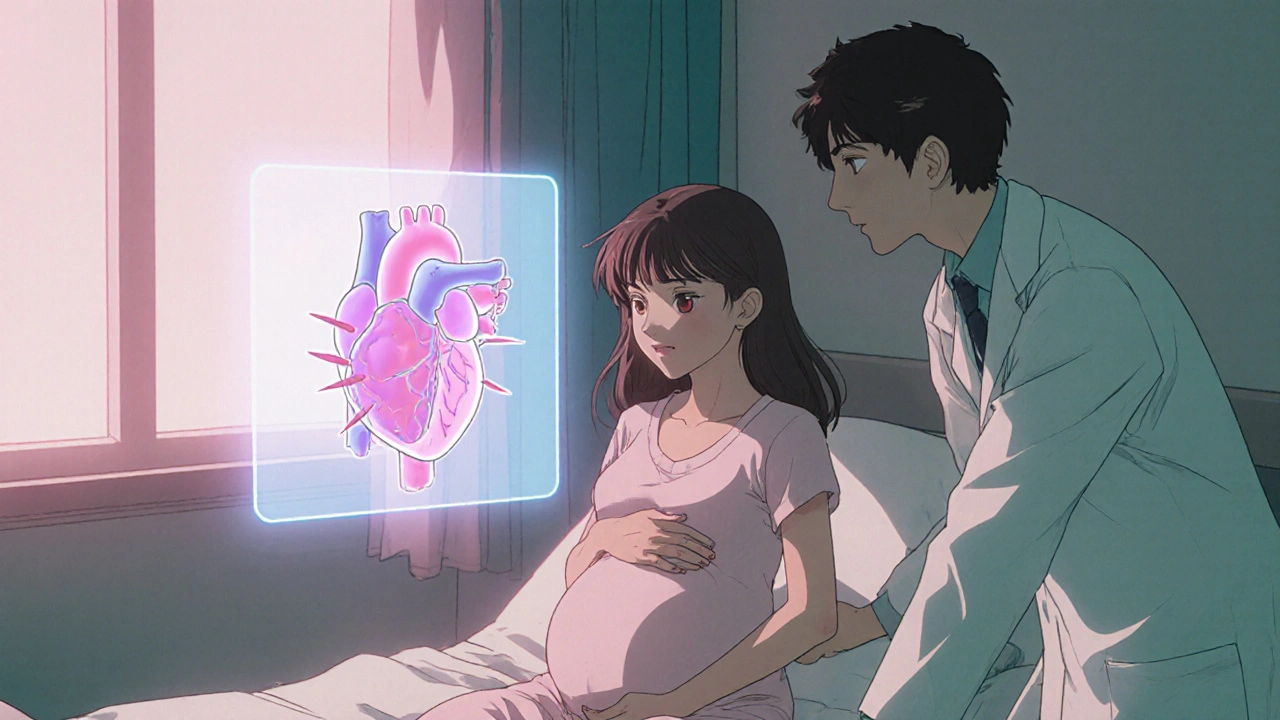

When a woman discovers she’s pregnant and is also diagnosed with pheochromocytoma, the news can feel overwhelming. This rare adrenal tumor releases large bursts of catecholamines that drive sudden spikes in blood pressure, heart rate, and sweat. Understanding how the condition behaves in pregnancy, spotting warning signs early, and coordinating a safe treatment plan are the three pillars that protect both mother and baby.

What Is Pheochromocytoma and How Common Is It in Pregnancy?

Pheochromocytoma is a catecholamine‑producing tumor that originates in the adrenal medulla. While it accounts for less than 0.2 % of all hypertensive disorders, its prevalence rises to roughly 1 in 5,000-10,000 pregnancies. Because the tumor can remain silent for years, many women only discover it when blood pressure becomes uncontrollable during routine prenatal visits.

The hormonal shifts of pregnancy-especially the rise in estrogen and increased plasma volume-can amplify catecholamine effects, making crises more likely in the third trimester. That’s why obstetricians and endocrinologists treat any pregnant patient with a confirmed tumor as high‑risk.

Key Symptoms and How Doctors Diagnose the Condition

Typical signs overlap with common pregnancy complaints, which is why a high index of suspicion is crucial. Look for:

- Paroxysmal hypertension (sudden BP > 160/100 mmHg) that doesn’t respond to standard antihypertensives.

- Palpitations, pounding headache, or profuse sweating that appear in episodes.

- Chest pain or anxiety attacks that seem out of proportion to normal pregnancy discomfort.

If these patterns emerge, clinicians will order biochemical testing. A 24‑hour urine collection or plasma free metanephrine assay is the gold standard, with sensitivity above 95 %.

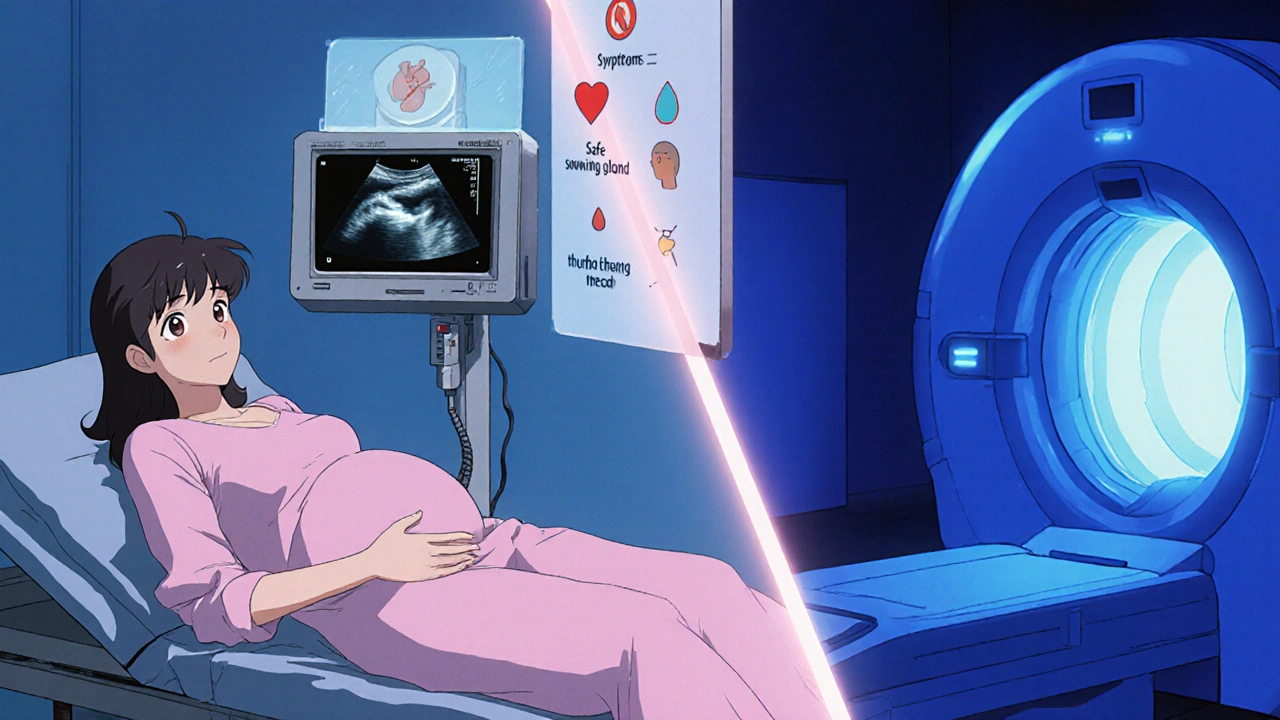

Imaging follows biochemical confirmation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without gadolinium is preferred because it avoids ionizing radiation, while abdominal ultrasound can offer a quick bedside view.

Maternal and Fetal Risks Without Proper Management

Uncontrolled pheochromocytoma carries serious stakes. Maternal mortality rates can reach 15 % in untreated cases, mainly due to hypertensive emergencies, stroke, or cardiac arrhythmias. For the fetus, risks include:

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) from chronic placental hypoperfusion.

- Preterm birth triggered by maternal crisis.

- Neonatal catecholamine overload leading to respiratory distress.

These outcomes underscore why multidisciplinary care-linking obstetrics, endocrinology, anesthesia, and neonatology-is the standard of care.

Medical Management: Which Drugs Are Safe During Pregnancy?

Controlling catecholamine surges is the first therapeutic goal. Alpha‑blockers are the cornerstone, with phenoxybenzamine or the shorter‑acting prazosin commonly used. Starting at a low dose and titrating every 2-3 days helps avoid reflex tachycardia.

Once adequate alpha‑blockade is achieved (usually after 7-10 days), beta‑blockers such as labetalol or propranolol can be added to blunt heart‑rate spikes. Beta‑blockers must never precede alpha‑blockade; doing so can cause unopposed alpha‑vasoconstriction and a dangerous BP surge.

For patients with refractory hypertension, Metyrosine-a tyrosine‑hydroxylase inhibitor-may be tried, but data on fetal safety are limited, so it’s reserved for life‑threatening cases.

Throughout the medical regimen, daily home BP monitoring and frequent lab checks for electrolytes and glucose are essential. Adjustments often occur at each prenatal visit.

Surgical Options: When Is Adrenalectomy Feasible?

Definitive removal of the tumor via laparoscopic adrenalectomy offers the best long‑term cure, but timing is critical. The consensus among endocrine surgeons is:

| Trimester | Preferred Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| First (0‑13 weeks) | Delay surgery if stable; use meds. | Risk of miscarriage from anesthesia. |

| Second (14‑27 weeks) | Optimal window for laparoscopic removal. | Uterus still low; fetal exposure minimal. |

| Third (28‑40 weeks) | Plan delivery first, then surgery postpartum. | Uterine size hampers access; risk of obstetric hemorrhage. |

If a crisis occurs in the third trimester, emergent surgery may be needed, but most teams aim to stabilize with medication and schedule a Cesarean delivery followed by immediate tumor excision.

Delivery Planning: Vaginal Birth vs. Cesarean Section

Both delivery routes are possible, but the choice hinges on tumor control and anesthetic safety. When alpha‑blockade is adequate and BP is stable, a carefully monitored vaginal delivery can proceed, often with an epidural to blunt sympathetic responses.

However, many specialists prefer a scheduled Cesarean section at 36‑38 weeks for several reasons:

- Allows a controlled environment for rapid conversion to surgery if a hypertensive crisis erupts.

- Reduces the stress of labor‑induced catecholamine surges.

- Facilitates immediate postoperative monitoring of both mother and newborn.

An experienced obstetric anesthesiologist will use short‑acting agents like etomidate and nitroprusside to keep blood pressure steady during induction.

Postpartum Care and Long‑Term Follow‑Up

Even after a successful delivery and tumor removal, vigilance doesn’t end. Follow‑up includes:

- Weekly BP checks for the first month, then monthly for six months.

- Plasma metanephrine levels at 6‑week and 6‑month intervals to confirm remission.

- Genetic counseling if the tumor is linked to MEN 2, VHL, or NF1 syndromes.

- Breast‑feeding considerations: most alpha‑ and beta‑blockers are compatible, but phenoxybenzamine is usually avoided.

Because recurrence can occur years later, lifelong annual screening is recommended, especially for women with a family history of endocrine tumors.

Checklist: What to Discuss With Your Care Team

- Current BP trends and medication side‑effects.

- Timing of biochemical testing and imaging results.

- Preferred delivery method and anesthesia plan.

- Plan for immediate postoperative monitoring of the newborn.

- Genetic testing options and implications for future pregnancies.

Bring this list to each appointment; clear communication reduces the chance of a surprise crisis.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can pheochromocytoma cause a miscarriage?

Severe, uncontrolled hypertension can increase the risk of placental abruption and miscarriage. Prompt medical control of catecholamine surges dramatically lowers this risk.

Is it safe to breast‑feed while on alpha‑blockers?

Phenoxybenzamine is not recommended during lactation, but shorter‑acting agents like prazosin have limited milk transfer and are generally considered compatible. Always consult your pediatrician.

What are the warning signs of a hypertensive crisis during labor?

A sudden BP rise above 180/120 mmHg, pounding headache, profuse sweating, and rapid heartbeat are red flags. Notify the anesthesiology team immediately.

Can the tumor be monitored without surgery?

Medical therapy can control symptoms, but the tumor remains a source of future crises. Definitive surgical removal is the recommended cure, especially after delivery.

What genetic conditions are linked to pheochromocytoma?

Mutations in RET (MEN 2), VHL, NF1, and SDHx genes can predispose patients. A genetics referral helps assess familial risk and guide testing for relatives.

By staying informed, collaborating with a dedicated care team, and following a clear plan, most women with pheochromocytoma can look forward to a safe pregnancy and a healthy baby.

Jennell Vandermolen - 23 October 2025

Thanks for the detailed rundown – staying on top of blood‑pressure trends and keeping the care team in sync can make a huge difference for mom‑and‑baby outcomes.

Mike Peuerböck - 7 November 2025

Indeed, the pharmacologic choreography resembles a finely tuned symphony; initiating phenoxybenzamine at a low dose and titrating gradually safeguards against reflex tachycardia while establishing a robust alpha‑blockade before beta‑agents are introduced.

Michaela Dixon - 22 November 2025

The interplay between endocrine dynamics and obstetric physiology is fascinating, especially when one considers that catecholamine surges can mimic ordinary pregnancy discomforts, which often delays diagnosis; therefore, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion whenever paroxysmal hypertension resists standard therapy, and they should promptly order a 24‑hour urine metanephrine panel to confirm the biochemical picture; imaging with MRI, devoid of gadolinium, offers a safe window into the adrenal landscape and helps delineate tumor size, which can influence surgical timing; genetics should not be overlooked, as germline mutations in RET, VHL, NF1, or SDHx genes not only predispose to pheochromocytoma but also have implications for family screening and future pregnancies; once the diagnosis is locked in, a multidisciplinary team comprising obstetrics, endocrinology, anesthesiology, and neonatology can devise a coordinated plan that balances maternal safety with fetal maturity; alpha‑blockade remains the cornerstone of pre‑operative preparation, with phenoxybenzamine or prazosin titrated over a week to achieve a target seated blood pressure below 130/80 mmHg; only after adequate alpha‑blockade should beta‑blockers like labetalol be added to temper tachycardia, avoiding the peril of unopposed alpha‑vasoconstriction; for refractory cases, metyrosine may be considered, albeit with cautious fetal monitoring due to limited safety data; surgical excision is ideally performed in the second trimester when the uterus is still low, allowing laparoscopic access and minimizing obstetric complications, while third‑trimester crises may necessitate emergent surgery followed by immediate cesarean delivery; delivery planning should account for tumor control, with many centers favoring a scheduled cesarean at 36‑38 weeks to provide a controlled environment for rapid blood‑pressure management and potential tumor resection; epidural analgesia can blunt sympathetic responses during labor if vaginal delivery is pursued, but continuous hemodynamic monitoring is essential regardless of route; postpartum care does not end with delivery; weekly blood‑pressure checks for the first month, then monthly surveillance, coupled with plasma metanephrine testing at six weeks and six months, ensure early detection of recurrence; lactation considerations permit most short‑acting alpha‑ and beta‑blockers, yet phenoxybenzamine is usually avoided due to its prolonged half‑life; finally, lifelong annual screening is prudent, especially for patients with a hereditary syndrome, to catch late recurrences and safeguard future pregnancies.

Dan Danuts - 6 December 2025

Great point about the teamwork – having an endocrinologist, obstetrician, and anesthesiologist all on the same page really cuts down the panic factor when a crisis hits.

Dante Russello - 21 December 2025

Absolutely, Dan, the synergy you mention, is the lifeline; when specialists communicate early, medication adjustments happen swiftly, and the patient feels supported, which in turn reduces stress‑induced catecholamine spikes, creating a positive feedback loop for both mother and baby.

Jinny Shin - 5 January 2026

Behold, the silent specter that stalks the pregnant womb, a nefarious adrenal phantom that masquerades as ordinary malaise, yet when it reveals its true ferocity, the heavens themselves seem to tremble under the weight of unchecked catecholamines.

deepak tanwar - 19 January 2026

While the narrative extols surgical removal as the definitive cure, one must question whether the timing recommendations truly reflect patient autonomy, or merely a prescriptive protocol that discounts individual risk assessments.

Abhishek Kumar - 3 February 2026

Looks fine.

hema khatri - 18 February 2026

Indeed, it’s heartening to see Indian physicians pioneering such protocols, and we must celebrate the expertise, dedication, and cultural sensitivity they bring to managing these rare cases, which often get overlooked in Western literature!