Every day, pharmacists make decisions that can mean the difference between a patient getting better or suffering harm. One of the most common-and most risky-choices is whether to substitute a brand-name drug with a generic version. It’s not just about saving money. It’s about legal exposure, patient safety, and knowing exactly where your responsibility begins and ends.

Why Generic Substitution Isn’t as Simple as It Seems

Generic drugs are cheaper. That’s the whole point. In the U.S., 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics, saving the system over $1.6 trillion between 2009 and 2018. But here’s the catch: just because a generic is approved by the FDA doesn’t mean it’s identical in every way to the brand-name drug. The FDA requires generics to be bioequivalent, meaning they deliver the same active ingredient at the same rate and amount as the brand. That sounds solid-until you realize that bioequivalence allows for a 20% variation in absorption. For most drugs, that’s fine. For others, it’s dangerous. Take levothyroxine, for example. It’s used to treat hypothyroidism. Even a tiny change in blood levels can cause fatigue, weight gain, or worse. A 2017 study in Epilepsy & Behavior found that 18.3% of patients had therapeutic failure after switching from brand to generic levothyroxine. Another study in JAMA Internal Medicine showed patients on generic antiepileptic drugs had a 7.9% higher risk of seizures. These aren’t rare cases. They’re predictable outcomes when you ignore the nuances of drug formulation.The Legal Trap: Who’s Responsible When Something Goes Wrong?

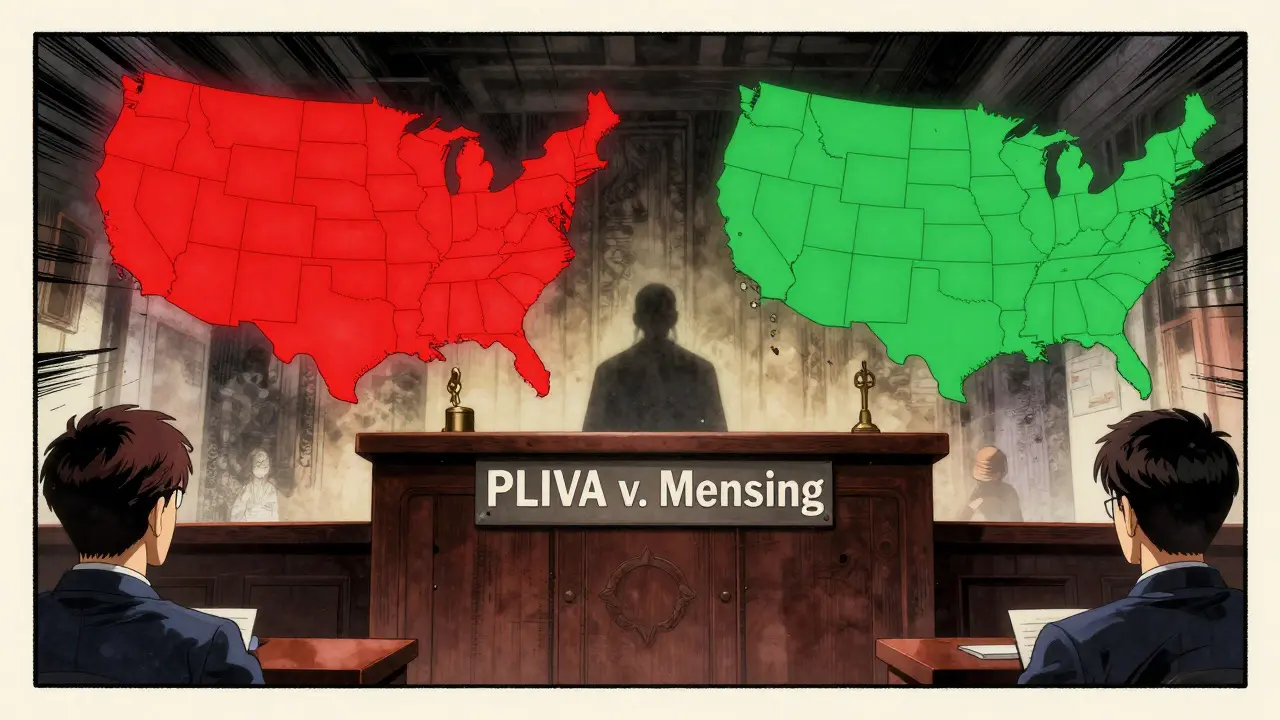

Here’s where it gets messy. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in PLIVA v. Mensing that generic drug manufacturers can’t be sued under state law for failing to update warning labels. Why? Because federal law forces them to use the exact same label as the brand-name drug. They can’t change it-even if new safety data emerges. This created a legal black hole. If a patient is harmed by a generic drug, they can’t sue the maker. And they usually can’t sue the brand-name maker either, because they didn’t produce the drug. That leaves the pharmacist. But here’s the twist: in 27 states, pharmacists are protected from greater liability when they substitute a generic. In 23 others, they’re not. In Connecticut, for instance, pharmacists can be held liable even if they followed the law. In Texas, they’re shielded-as long as they follow the rules. This isn’t just a legal theory. It’s real. In 2019, a patient suffered permanent neurological damage after a generic antiepileptic was substituted. The court dismissed the case. Why? Because federal preemption blocked liability against the manufacturer. The pharmacist wasn’t named in the suit. No one was held accountable. The patient lost. The system failed.State Laws Vary Wildly-And So Does Your Risk

You can’t treat generic substitution the same way in every state. The rules differ across four key areas:- Duty to substitute: 27 states require you to substitute unless the prescriber says no. 23 states let you decide.

- Notification: Only 18 states require you to tell the patient directly-beyond just putting a label on the bottle.

- Consent: 32 states let patients refuse substitution. But do they even know they have that right?

- Liability protection: 27 states protect you from being sued more than if you’d dispensed the brand. 23 don’t. That’s a huge gap.

What Pharmacists Are Doing to Protect Themselves

Most pharmacists aren’t waiting for lawmakers to fix this. They’re taking action. A 2022 survey of 452 pharmacists found 74% have refused to substitute a generic for a narrow therapeutic index drug-even when the law allowed it-because they were scared of liability. Here’s what the most cautious pharmacies are doing:- Know your state law: The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy updates its compendium annually. Bookmark it. Check it every January.

- Use EHR alerts: Set up your electronic health record to flag drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, and cyclosporine. These are the high-risk ones.

- Get written consent: If your state allows refusal, use a standardized form. Don’t rely on a verbal nod. Document it.

- Communicate with prescribers: If you’re unsure, call the doctor. Many are unaware of the risks too.

- Track every substitution: Log the brand, generic, lot number, and patient. If something goes wrong, you need proof you followed protocol.

- Update your insurance: Standard malpractice policies may not cover substitution-related claims. Ask your provider for supplemental coverage.

- Train your staff: Pharmacy technicians need to know the rules too. A misstep by anyone on your team can land you in court.

Patient Confusion Is a Hidden Risk

Patients don’t understand substitution. A 2022 Johns Hopkins survey found 63% couldn’t name their state’s substitution laws. The Patient Advocacy Foundation found 41% didn’t know their prescription had been switched until they felt worse. On Reddit’s r/pharmacy, a thread with over 4,000 upvotes told the story of a woman whose thyroid levels crashed after switching to a generic. She didn’t know it was a substitution. Her pharmacist didn’t tell her. This isn’t just about ethics. It’s about liability. If a patient suffers harm and claims they weren’t informed, and your state requires notification, you’re exposed. Even if you followed the law, if you didn’t document it properly, you’re in trouble.

The Bigger Picture: Where Is This All Headed?

The system is under pressure. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the current liability gap costs $4.2 billion a year in untreated adverse events. The FDA’s 2023 pilot program for label changes has approved 68% of requests-but only 12% came from generic manufacturers. They’re still waiting for federal permission to act. Eleven states introduced the Generic Drug Safety Act in 2023. It would require brand-name manufacturers to update labels within 30 days of new safety data, and generics to adopt those changes within 60 days. If passed, it could finally close the legal gap. But it’s still in committee. In the meantime, the most promising solution is the consensus labeling model proposed by Dr. Aaron Kesselheim. Imagine one standardized label, agreed upon by all manufacturers and updated by a central body. No more conflicting warnings. No more legal confusion. Five states are piloting this under the Interstate Pharmacy Compact.Bottom Line: Your Risk, Your Responsibility

Generic substitution saves money. It saves lives. But it also creates legal landmines. You can’t avoid it. But you can control how you handle it. Stop assuming all generics are equal. Know which drugs are high-risk. Know your state’s laws. Document everything. Talk to patients. Talk to prescribers. Update your insurance. Train your team. The law won’t fix this for you. The FDA won’t fix this for you. Only you can protect yourself-and your patients-by doing the work.Can a pharmacist be sued for substituting a generic drug?

Yes, but only under certain conditions. In 23 U.S. states, pharmacists have no legal protection from liability if a patient is harmed by a generic substitution. Even in states with protections, liability can arise if the pharmacist failed to follow state notification or consent rules. Federal law blocks lawsuits against generic manufacturers, so patients often turn to pharmacists as the only viable target.

Which drugs are most dangerous to substitute with generics?

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index are the highest risk. These include levothyroxine (for thyroid disorders), warfarin (a blood thinner), phenytoin and other antiepileptics, cyclosporine (for transplant patients), and lithium. Even small changes in blood levels can cause serious harm. Studies show substitution in these drugs leads to therapeutic failure in up to 18% of cases.

Do I need to get patient consent before substituting a generic?

In 32 states, patients have the right to refuse substitution. But you’re only legally required to obtain consent in 18 states if you must notify them directly. Even if your state doesn’t require it, getting written consent is the safest practice. Many pharmacists use a simple form signed by the patient to document their choice.

Is generic substitution always cheaper for patients?

Usually, yes-but not always. For common drugs like statins or metformin, generics save patients an average of $327.50 per year. But for high-risk drugs like levothyroxine, some patients end up paying more due to follow-up visits, lab tests, or hospitalizations caused by adverse effects from substitution. The real cost isn’t just the price tag-it’s the downstream impact on health.

What should I do if a patient reports side effects after switching to a generic?

Take it seriously. Document the symptoms, date, and medication details. Contact the prescriber immediately. Offer to switch back to the brand-name drug if possible. Review your substitution logs to confirm you followed all state requirements. If the patient was not properly notified, you may be at legal risk. Never dismiss patient reports-even if the drug is "bioequivalent." Real-world effects matter more than lab standards.

Are biosimilars next for substitution liability issues?

Yes. Forty-five states now allow biosimilar substitution, but liability rules are inconsistent. Biosimilars are even more complex than traditional generics-they’re made from living cells, not chemicals. The FDA has approved only 28% of them for substitution so far. As adoption grows, pharmacists will face the same legal gray zones: who’s responsible if a biosimilar causes harm? The answer isn’t clear yet, but the risk is rising.

How often should I review my pharmacy’s substitution policies?

At least once a year, and immediately after any state law changes. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy updates its state compendium annually in January. Many states pass new substitution laws each legislative session. A policy that was compliant last year may be outdated today. Set a calendar reminder. Don’t wait for a lawsuit to prompt you to act.