More than 40% of older adults take five or more medications every day. That’s not just common-it’s dangerous. Polypharmacy isn’t just about having a lot of pills. It’s about the hidden risks: falls, confusion, kidney damage, and even premature death. And it’s happening because the system isn’t built to handle it. Your grandma might be on blood pressure meds, diabetes pills, a sleep aid, an arthritis drug, and a stomach protector-all prescribed by different doctors, with no one stepping back to ask: Do you really need all of these?

Why Polypharmacy Is a Silent Crisis

Polypharmacy means taking five or more medications regularly. It’s not a diagnosis. It’s a symptom of a broken system. Older adults often see multiple specialists: a cardiologist for the heart, a neurologist for memory, a rheumatologist for joints, a gastroenterologist for reflux. Each one adds a prescription. No one looks at the whole picture. By age 65, the average person takes 5.8 prescriptions a year. That’s up from 2.8 in 1988. In nursing homes, 91% of residents are on five or more drugs. And it’s not just prescriptions. Many take over-the-counter painkillers, herbal supplements, or sleep aids-none of which are tracked in the main medical record. The real danger isn’t the number of pills. It’s what happens when those pills interact. A 2020 study found that 10% of hospital admissions in seniors are caused by bad drug reactions. That’s tens of thousands of people every year who end up in the ER because a medication they were told to take made them worse.How Aging Changes Your Body’s Response to Drugs

Your body doesn’t process medicine the same way at 75 as it did at 45. Liver function drops by 30-50% after 80. Kidneys clear drugs slower-about 1% less per year after age 40. That means drugs stick around longer. They build up. Even a normal dose can become toxic. Certain drugs are especially risky. Benzodiazepines like Xanax or Valium increase fall risk by 50%. NSAIDs like ibuprofen raise the chance of stomach bleeding by 2.5 times. Anticholinergics-used for overactive bladder, allergies, or depression-can make memory worse and raise dementia risk by 50% over seven years. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria lists 56 medications that are too risky for seniors. Many are still prescribed because doctors don’t know the list-or because they’re unaware the patient is taking them.Deprescribing: The Missing Step in Senior Care

Most people assume more drugs = better care. But the opposite is often true. Deprescribing isn’t about stopping meds blindly. It’s about removing what’s no longer helping-or what’s doing more harm than good. A 2021 Duke Health review showed that when done right, deprescribing cuts adverse drug events by 22% and hospital stays by 17%. That’s not a small gain. That’s life-changing. The process starts with a question: What’s the goal of this medication? Is it to prevent a heart attack? To ease pain? To help sleep? If the patient’s goal is to stay independent at home, not to live longer with 10 pills a day, then some meds may no longer fit. High-risk drugs are usually the first to go: opioids, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, and long-term proton pump inhibitors (which can weaken bones). A 2023 update to the Beers Criteria even recommends stopping antipsychotics in dementia patients-reducing death risk by 19%.

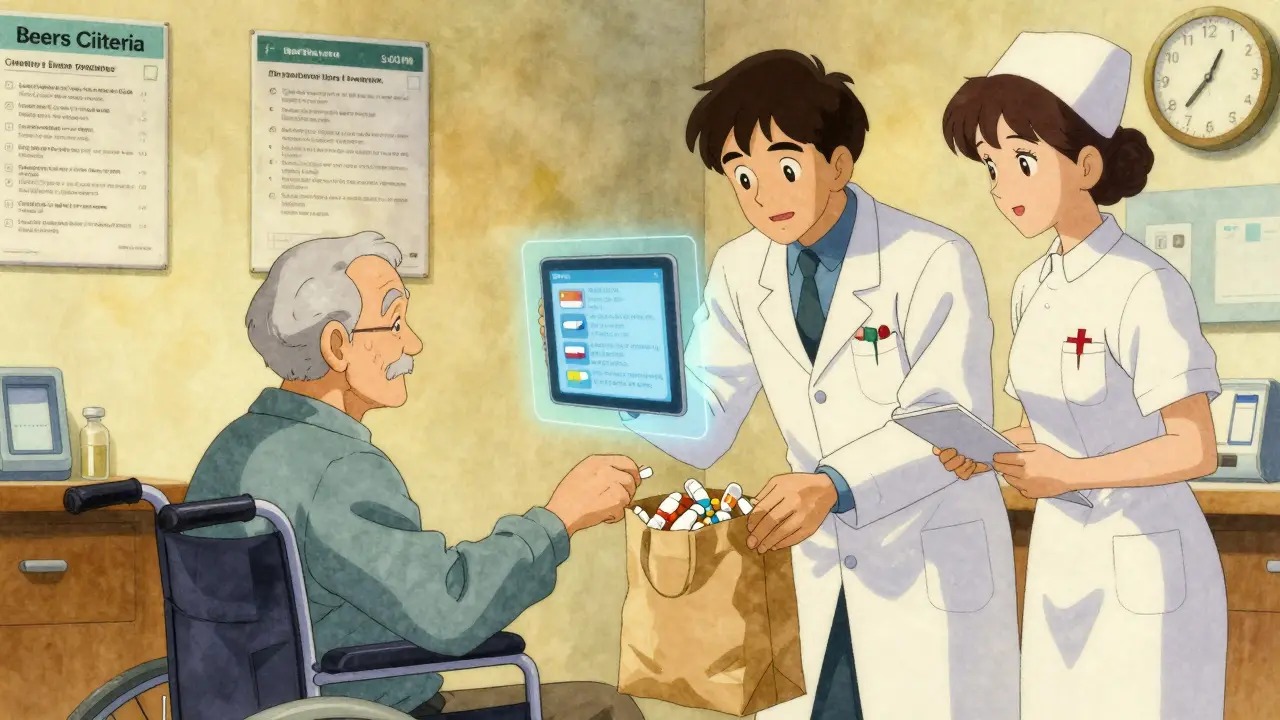

The Brown Bag Review: A Simple Fix That Works

One of the most effective tools is the “brown bag review.” Ask the patient to bring every pill, capsule, patch, and bottle-prescription, OTC, herbal, even the ones they haven’t taken in months-to their doctor’s visit. In real-world clinics, this simple act finds 2.8 unnecessary or duplicate medications per person. One man came in with 17 pills. After the review, 8 were stopped. His confusion cleared. His balance improved. He went from falling twice a month to zero falls in six months. This isn’t magic. It’s basic. If you don’t know what’s in the bag, you can’t know what’s hurting the patient.Who Should Be on the Team?

Managing polypharmacy isn’t a job for one doctor. It needs a team. A 2019 study showed that when pharmacists, nurses, and doctors work together, medication safety improves by 32% compared to solo care. Pharmacists are key. They can spot interactions you’d miss. Medicare now pays for Medication Therapy Management (MTM) for seniors on multiple drugs. Yet only 15% of eligible patients get it. A pharmacist can sit down with a patient and say: “This blood pressure pill and this diuretic are both making you dizzy. Let’s try one instead of two.” Or: “You’re taking two different painkillers that do the same thing. You don’t need both.” Nurses help with daily routines. They can create simple pill organizers. They can call to check if the patient is taking meds correctly. And the patient? They need to be heard. Only one in three seniors talk to their doctor about what they want from treatment. Do they want to live longer? Or do they want to eat dinner without nausea, sleep through the night, or walk to the mailbox without falling?

Technology Isn’t the Answer-But It Can Help

Electronic health records are supposed to prevent bad interactions. But they’re full of false alarms. One study found 78% of drug interaction alerts are wrong. Doctors learn to ignore them. New tools are changing that. The FDA-approved MedWise platform uses genetic data to predict how a person will react to specific drugs. In a 2022 trial, patients using it had 41% fewer adverse events. Apps that track meds, send reminders, and flag duplicates are growing. But they only work if the patient uses them-and if the data gets into the medical record. The real breakthrough? The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services launched the “Deprescribing for Better Outcomes” initiative in January 2023. They’re funding 15 health systems to build standardized plans. That’s the first time the government is treating this as a systemic problem-not just a patient issue.What Families Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Here’s what you can do:- Ask for a full medication list-every pill, every supplement-and keep a copy.

- Go to appointments with your parent or loved one. Take notes.

- Ask: “Why is this medicine still being used? What’s it for? What happens if we stop it?”

- Check for duplicate meds. Is there more than one drug for the same condition?

- Watch for side effects: dizziness, confusion, falls, loss of appetite, constipation.

- Don’t assume more is better. Sometimes less is safer.

The Future: From Quantity to Quality

The next big shift isn’t about counting pills. It’s about matching drugs to the person-not just their age, but their biology, their goals, and their life. Geropharmacogenomics-the study of how genes affect drug response in older adults-is still new. But early data shows it could cut adverse events by half in people who’ve been genetically tested. The National Institute on Aging is funding 12 long-term studies to find the best way to manage meds for seniors with multiple chronic conditions. They’re looking at quality of life-not just survival. In five years, we may not talk about “polypharmacy” anymore. We’ll talk about “personalized medication plans.” And the goal won’t be to take the most drugs. It’ll be to take the right ones-and stop the rest.What is polypharmacy in elderly patients?

Polypharmacy in elderly patients means taking five or more medications regularly. It’s not just about the number-it’s about the risks. Older adults are more sensitive to drug side effects due to slower metabolism and kidney function. This increases the chance of falls, confusion, kidney damage, and hospital visits. Many medications prescribed for one condition can interfere with others, especially when multiple doctors are involved.

Is polypharmacy always harmful?

Not always. Some seniors need multiple medications to manage serious conditions like heart failure, diabetes, or high blood pressure. The problem isn’t having many drugs-it’s having drugs that aren’t needed, are duplicated, or are too risky for their age. The goal isn’t to cut all meds, but to remove the ones doing more harm than good. This is called deprescribing.

What are the most dangerous medications for seniors?

According to the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria, the most risky drugs for older adults include benzodiazepines (like Valium), NSAIDs (like ibuprofen), anticholinergics (used for bladder or allergy issues), opioids, and long-term proton pump inhibitors (for heartburn). These can cause falls, memory loss, stomach bleeding, or bone fractures. Many are still prescribed because doctors aren’t aware of the updated guidelines.

What is deprescribing, and how does it work?

Deprescribing is the planned, safe stopping of medications that are no longer beneficial or are causing harm. It’s not done all at once. A doctor or pharmacist reviews each drug, asks if it’s still needed, and gradually reduces or removes it-watching for side effects. Studies show it reduces hospital stays by 17% and adverse reactions by 22%. It’s most effective when the patient’s goals (like staying independent or avoiding dizziness) guide the decision.

How can families help manage senior medications?

Families can make a big difference. Bring all medications-prescription, over-the-counter, and supplements-to doctor visits. Ask: Why is this medicine still being used? Is there a cheaper or safer option? Watch for new symptoms like confusion, dizziness, or loss of appetite. Use pill organizers and set reminders. Don’t assume more pills mean better care. Sometimes, fewer meds mean a better quality of life.

Can technology help reduce polypharmacy risks?

Yes, but not perfectly. Electronic health records often flood doctors with false drug interaction alerts-78% of them are wrong. New tools like MedWise use genetic data to predict how a person will react to specific drugs, and have reduced adverse events by 41% in trials. Apps that track meds and send reminders help, but only if the data is shared with the care team. The best tech supports human judgment-it doesn’t replace it.

Anna Pryde-Smith - 23 January 2026

This is insane. My grandma took 14 pills a day. No one ever asked if she needed them. She was confused, falling, barely eating-and the doctors just kept adding more. One day, her pharmacist looked at her brown bag and said, 'You’re taking two different versions of the same blood pressure med.' She stopped one. Within a week, she was herself again. Why does it take a pharmacist to do what doctors won't? This system is broken, and it’s killing people quietly.

Oladeji Omobolaji - 24 January 2026

Man, this hit home. In Nigeria, we don’t even have enough meds for people, but here, folks get too many and no one checks if they work together. I saw my uncle on 8 drugs-he couldn’t walk straight. Took his daughter to the clinic with his whole pill box, and they cut 4. He started cooking again. Simple fix. Why isn’t this standard everywhere?

Dawson Taylor - 26 January 2026

The fundamental issue is not polypharmacy per se, but the absence of holistic, patient-centered pharmacotherapy. The biomedical model fragments care into organ-specific silos, while pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in aging demand integrative oversight. Deprescribing is not merely de-prescribing-it is therapeutic recalibration aligned with patient values. The Beers Criteria are necessary, but insufficient without implementation science.

charley lopez - 26 January 2026

While the clinical imperative for deprescribing is well-documented, the operational barriers remain substantial: fragmented EHR systems, inadequate reimbursement for medication reconciliation, and cognitive biases among prescribers favoring intervention over omission. The 78% false-positive alert rate in clinical decision support systems further erodes clinician trust in technology-mediated safety nets. A systems-level redesign is required, not merely behavioral nudges.

Kerry Evans - 27 January 2026

Let’s be honest-this isn’t about medicine. It’s about greed. Pharma companies push pills. Doctors get paid for prescribing, not for stopping them. Insurance doesn’t cover time spent reviewing meds. And patients? They’re conditioned to believe more drugs = better care. It’s a perfect storm of profit-driven negligence. Someone needs to sue these companies and hospitals. People are dying because of corporate indifference.

Susannah Green - 27 January 2026

PLEASE-every family member, PLEASE do the brown bag review. I did it with my mom. She had three different OTC sleep aids, two different ibuprofen brands, and a melatonin patch she forgot she was using. We got rid of all of them. She sleeps better now. She doesn’t feel foggy. She walks without a cane. It’s not rocket science. Just show up. Bring the bag. Ask the questions. You can save someone’s life. Seriously.

Kerry Moore - 27 January 2026

The data presented here is compelling, yet the emotional dimension of deprescribing is often underemphasized. For many elderly patients, medications represent security, control, or even identity. Removing a pill may trigger existential anxiety-even when clinically appropriate. A compassionate, iterative approach, grounded in shared decision-making, is not merely preferable-it is ethically mandatory.

Janet King - 28 January 2026

I’m a nurse in a senior center. We do brown bag reviews every month. We find duplicate meds, expired pills, and drugs the patient hasn’t taken in years. One woman had a blood pressure pill she was told to stop in 2018. She took it every day until we found it. She cried when we told her she could stop. Said she felt like a fraud. We need more of this. Not more drugs. More listening.

Vanessa Barber - 29 January 2026

Actually, I think this whole 'polypharmacy crisis' is overblown. My dad’s on 8 meds. He’s 82. He’s hiking, gardening, playing chess. He’s fine. Maybe the real problem is doctors who think seniors are fragile. Maybe we’re just pathologizing normal aging.

Sallie Jane Barnes - 29 January 2026

To the person who said this is overblown: I lost my mother to a drug interaction. She was on a statin, an NSAID, and an anticholinergic. No one asked her if she needed all three. She had a GI bleed and never woke up. This isn’t theory. It’s real. Please don’t minimize it. If you have a loved one on multiple meds-ask. Now. Don’t wait for the ER.

Andrew Smirnykh - 30 January 2026

In Japan, we have 'chiropractic pharmacists' who visit elderly homes weekly to review meds. No one has to drive. No one has to remember. They just come with a checklist. It’s part of the national health plan. Why don’t we do this here? We have the technology. We have the data. We just don’t prioritize human dignity over efficiency.