When someone is diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, the conversation doesn’t start with treatment options-it starts with a question: How much time do I have? The answer isn’t simple. Huntington’s isn’t like a broken bone or even most cancers. It doesn’t come on suddenly. It creeps in. First, it’s a twitch in the finger. Then, a stumble on the stairs. Then, the words start slipping. And behind all of it, a ticking genetic clock that doesn’t stop, no matter what you do.

How Huntington’s Disease Is Passed Down

Huntington’s disease is inherited in a way that’s almost cruelly straightforward. If one parent has it, each child has exactly a 50% chance of getting the faulty gene. No exceptions. No luck. No second chances. It doesn’t skip generations. It doesn’t care if you’re male or female. It just shows up-when it’s ready.

The problem lies in a tiny glitch in the HTT gene on chromosome 4. Normally, this gene has a string of CAG repeats-10 to 26. But in Huntington’s, that number balloons. If you have 40 or more, you will develop the disease. Between 36 and 39, you might or might not. And 27 to 35? You won’t have symptoms, but your kids could inherit a version that does.

Here’s what makes it worse: when the gene comes from the father, the repeats tend to grow bigger. That’s why 85% of juvenile Huntington’s cases-those starting before age 20-come from dads. A father with 45 repeats might pass on 55. That’s not just a higher risk. It’s a faster clock. Kids with 60+ repeats often show signs before age 10. Their bodies break down quicker. Their minds fade faster.

Genetic testing can tell you if you carry the mutation. But 72% of people at risk delay testing until symptoms appear. Why? Because knowing doesn’t change the outcome. It only changes how you live with the waiting.

What Chorea Really Looks Like

Chorea is the signature of Huntington’s. Not the whole disease-but the part people notice first. It’s not a tremor. It’s not a spasm. It’s involuntary movements that look like dancing. A shoulder shrugs. A hand flings out. A foot taps. Then it moves to the face-eyelids blink too fast, the mouth twists. It’s unpredictable. It doesn’t follow a pattern. And it disappears when you sleep.

Doctors measure it using the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS). A score of 1 means mild, barely noticeable. A 4 means constant, uncontrollable motion across the whole body. Early on, chorea is mostly in the hands and feet. Later, it spreads. And then, something else happens: the dancing stops. Not because it’s getting better. Because the muscles are too worn out. The chorea fades into stiffness, slowness, and rigidity. That’s when walking becomes impossible.

The only FDA-approved drugs for chorea are tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine (Austedo). They reduce the movements by about 25-30%. But they come with a heavy cost: depression in 22% of users, drowsiness in 18%. Some patients refuse them-not because they don’t work, but because they feel like they’re losing more of themselves. The chorea is part of their identity now. Taking it away feels like erasing what’s left.

There’s also valbenazine (Ingrezza), approved in 2023. It works similarly but with fewer side effects. Still, it doesn’t stop the disease. It just masks one symptom. And it costs thousands a month. Many patients skip it because insurance won’t cover it fully.

Care Planning Isn’t Optional-It’s Survival

Most people think Huntington’s is about medicine. It’s not. It’s about planning. Because no drug can stop the brain from dying. But a good care plan can help you live longer, better, and with more dignity.

At diagnosis, the first step isn’t a prescription. It’s a conversation. With a genetic counselor. With a social worker. With your family. You need to decide: Who will make decisions when you can’t? Where do you want to live as things get harder? Who will be your voice when words fail you?

By the time someone reaches five years after diagnosis, 78% of patients at specialized centers have legal documents in place-living wills, healthcare proxies, power of attorney. In general clinics? Only 37%. That gap isn’t just paperwork. It’s safety. It’s peace of mind. It’s avoiding court battles when your family disagrees on feeding tubes or ventilators.

By year 10, most people need help with basic tasks. Dressing. Eating. Bathing. That’s when occupational therapy and speech therapy become critical. Speech therapy doesn’t just help with slurring. It teaches you how to swallow safely. Aspiration pneumonia-inhaling food into the lungs-is the leading cause of death in late-stage HD. It’s preventable. But only if you’ve practiced the techniques.

By year 15, 89% of patients need full-time care. Many end up in nursing homes. But not because they want to. Because their families can’t manage it anymore. The average caregiver spends 15+ hours a week just coordinating appointments-neurologist, therapist, psychiatrist, dietitian. And that’s not counting the emotional toll.

Specialized Huntington’s centers cut hospital stays by 32% and reduce suicide risk by 58%. Why? Because they don’t treat symptoms. They treat the whole person. They know when to bring in palliative care. When to adjust meds. When to say, “It’s time to stop fighting.”

The Hidden Costs-Money, Time, and Grief

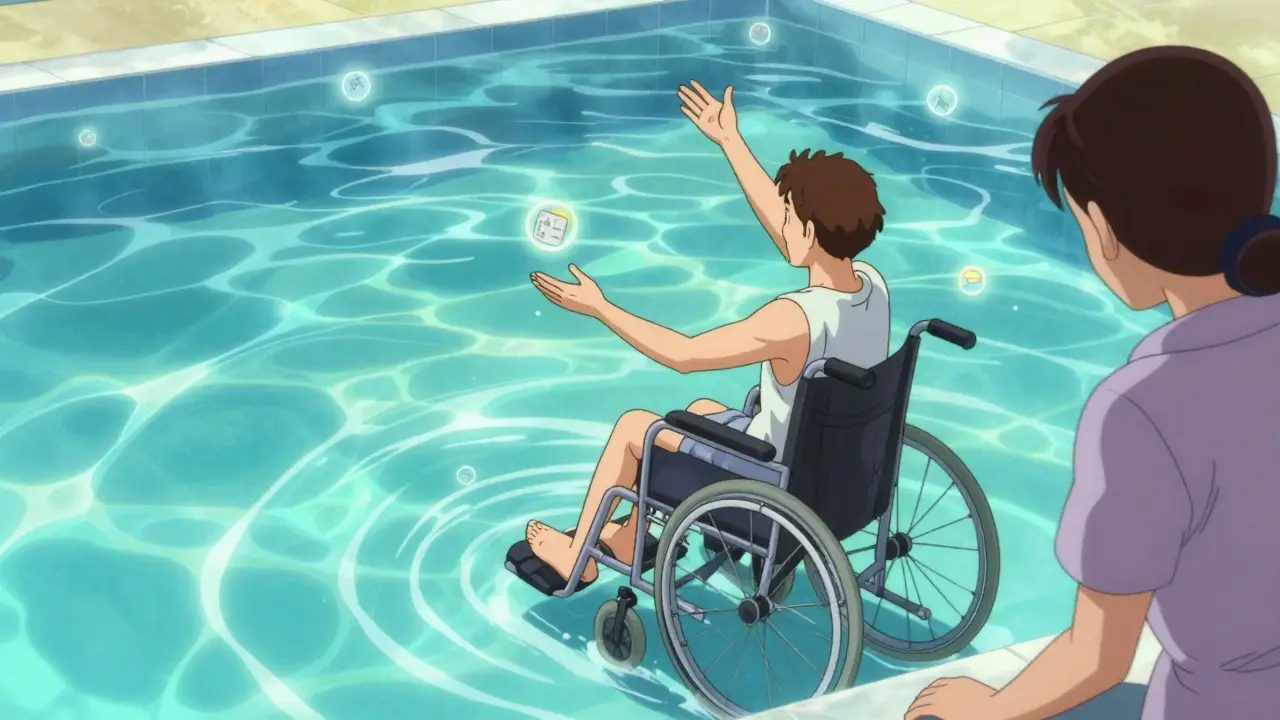

The average annual cost of care in the U.S. is $125,000. Insurance covers maybe half. The rest? Out of pocket. For many families, that means selling homes, draining savings, quitting jobs. One patient told the HDSA forum: “I had to take a second job just to pay for my wife’s aquatic therapy. She swims three times a week. It’s the only thing that keeps her moving.”

Aquatic therapy is 35% more effective than land-based therapy for balance. But only 32% of patients get it because it’s not covered. Physical therapy? Covered. But only if you can get to a clinic. In rural areas, the wait for a specialist is over two years. That’s two years of decline. Two years of lost time.

And then there’s the grief. Not just for the person with HD. For the whole family. A husband watches his wife forget how to tie her shoes. A child sees their parent forget their name. A sibling wonders: “Will I get it too?”

One mother on Reddit wrote: “I tell my daughter every day that I love her. Not because she might forget. But because I might forget to say it.”

What’s Changing-and What’s Not

There’s hope. Not in drugs yet. But in science. In 2023, a trial called SELECT-HD showed a 38% drop in the toxic huntingtin protein in patients after 135 weeks. That’s the first time a treatment has actually reduced the root cause. Roche’s tominersen, though paused and restarted, still holds promise. Gene therapies are coming. Maybe in 15 years, we’ll have something that slows or stops HD.

But here’s the hard truth: even if that happens tomorrow, it won’t help the 40,000 Americans living with HD right now. They still need care. They still need meals. They still need someone to hold their hand when they can’t speak. They still need families who know how to plan.

Right now, only 38% of U.S. neurologists follow the official care guidelines. Most don’t know how to start the conversation. Most don’t know what to do after diagnosis. That’s why the Huntington’s Disease Society of America is pushing to expand specialty centers-from 62% to 85% coverage by 2025.

But until then, the most powerful tool isn’t a drug. It’s a plan. Written down. Shared. Updated. And followed.

What You Can Do Today

If you or someone you love has been diagnosed:

- Find a Huntington’s Disease Center of Excellence-even if it’s hours away. They have teams trained in this disease. General neurologists don’t.

- Start care planning within six months. Not next year. Not when things get worse. Now.

- Complete a living will and healthcare proxy. Even if it feels too early.

- Connect with HDSA or the European Huntington’s Disease Network. They offer free counseling, support groups, and care guides.

- Ask about aquatic therapy. It’s not a luxury. It’s a lifeline.

- Don’t wait to talk to your family about the future. The silence is heavier than the diagnosis.

Huntington’s disease doesn’t give you much time. But it gives you enough to plan. And planning isn’t giving up. It’s choosing how you’ll live-right up until the end.

Is Huntington’s disease always inherited?

Yes. Huntington’s is caused by a single faulty gene passed from parent to child. There are no spontaneous cases. If you don’t have the gene from a parent, you cannot develop Huntington’s. However, about 10% of people diagnosed don’t know their parent had it-because the parent died young, never showed symptoms, or was misdiagnosed.

Can you test for Huntington’s before symptoms appear?

Yes. A blood test can detect the CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene. But testing is a major decision. Many at-risk people choose not to test because there’s no cure. Genetic counseling is required before testing to help people understand the emotional and practical impact. Only 15-20% of at-risk individuals get tested before symptoms.

Does chorea get worse over time?

Yes, but not in a straight line. Chorea peaks in the early to mid-stages and then often decreases as muscle weakness and stiffness (dystonia and rigidity) take over. This doesn’t mean the disease is improving. It means the brain is losing more control over movement. The later stages are marked by immobility, not excessive movement.

How long do people live after diagnosis?

On average, people live 15 to 20 years after symptoms begin. Juvenile cases progress faster-often 10 to 15 years. Death is usually caused by complications like pneumonia, heart failure, or injuries from falls. With comprehensive care, survival can be extended by up to 2.3 years. Care planning directly affects lifespan.

Is there a cure for Huntington’s disease?

No. There is no cure yet. Current treatments only manage symptoms-chorea, depression, irritability. But research is advancing. Gene-silencing therapies like tominersen and antisense oligonucleotides are in trials and show promise in reducing the toxic protein that causes brain damage. Even if a cure is found, it will likely help future patients first. For now, care planning is the most effective tool available.

Can lifestyle changes help with Huntington’s?

Yes, but not in the way you might think. Exercise doesn’t stop the disease, but it slows decline. Regular physical activity, especially aquatic therapy, improves balance, reduces falls, and boosts mood. A high-calorie diet helps because HD increases metabolism. Avoiding alcohol and stress helps manage chorea and mood swings. But these aren’t cures. They’re ways to make the journey more manageable.

What’s the difference between tetrabenazine and Austedo?

Both reduce chorea by blocking dopamine. Tetrabenazine (Xenazine) is older and cheaper but causes more drowsiness and depression. Austedo (deutetrabenazine) is a modified version with fewer side effects and once-daily dosing. It’s more expensive, but many patients tolerate it better. Valbenazine (Ingrezza), approved in 2023, is similar to Austedo and may be an alternative if others don’t work.

Why is care coordination so hard for families?

Because Huntington’s requires input from neurologists, therapists, psychiatrists, nutritionists, social workers, and genetic counselors-all at once. Most families don’t know who to call or how to organize appointments. Insurance doesn’t cover care coordination. And many doctors don’t communicate with each other. Specialized HD centers solve this with team-based care. Without them, families are left to manage chaos.

For families navigating Huntington’s, the hardest part isn’t the loss of movement or memory. It’s the loss of control. Over time. Over decisions. Over the future. But control isn’t about stopping the disease. It’s about choosing how you face it. And that’s something no gene can take away.

Madhav Malhotra - 12 January 2026

Man, this hit different. In India, we don’t talk much about genetic stuff like this-too much stigma, too little access. But I showed this to my cousin whose mom has HD. She cried for an hour, then made a spreadsheet of every specialist in Delhi. That’s power right there. Planning isn’t giving up-it’s fighting smarter.

Jennifer Littler - 14 January 2026

The UHDRS scoring is critical for longitudinal tracking, but in clinical practice, inter-rater reliability remains a persistent issue-especially when chorea fluctuates diurnally. Also, the pharmacokinetics of deutetrabenazine show reduced CYP2D6 metabolism, which is advantageous in polymorphic populations. Still, the cost-benefit analysis for valbenazine is questionable without Medicaid expansion in rural states.

Jason Shriner - 14 January 2026

so like… we’re just supposed to dance our way to death? 🤡

also why is everyone acting like this is news? my grandpa had it. he danced till he couldn’t stand. then he just… stopped. no big reveal. just quiet.

Alfred Schmidt - 16 January 2026

Why do people keep saying 'planning isn't giving up'? That’s the exact language they use before they euthanize dogs! You’re not 'choosing how you face it'-you’re being told to accept a death sentence and fill out paperwork while your brain melts! And don’t get me started on 'aquatic therapy'-like swimming in a pool is gonna stop your neurons from turning to mush! This is just corporate wellness propaganda wrapped in a sad story!

Vincent Clarizio - 17 January 2026

Let’s be real here-Huntington’s isn’t just a disease, it’s a metaphysical mirror. It forces us to confront the terrifying fragility of identity. When your body betrays you, when your words dissolve into gibberish, when your own child looks at you and doesn’t recognize the face that raised them-what’s left? Not genes. Not dopamine blockers. Not even love. Just the echo of who you were. And yet… we still write living wills. We still schedule aquatic therapy. We still say ‘I love you’ every day. Why? Because meaning isn’t found in survival-it’s carved into the act of showing up, even when you know the ending. The tragedy isn’t the disease. The tragedy is that we’re the only species that knows it’s coming… and still chooses to love anyway.

Sam Davies - 17 January 2026

Chorea as 'dancing'? How quaint. In the 19th century, they called it 'St. Vitus's Dance'-romanticized it like some tragic ballet. Now we’ve got Austedo and insurance battles. Progress? Or just better packaging for the same slow horror? Also, 125k a year? In the UK, we’d call that a luxury. Here, you get a GP who says 'take paracetamol' and a pamphlet titled 'Coping with Neurodegeneration (PDF)'.

Christian Basel - 19 January 2026

Most of this is common sense. Genetic testing delay? Yeah, people are scared. Care planning? Duh. But nobody talks about how the medical system actively discourages early intervention. Neurologists don’t get reimbursed for counseling. So they don’t do it. It’s not ignorance-it’s capitalism.

Alex Smith - 21 January 2026

Y’all are missing the point. This isn’t about drugs or costs or even chorea. It’s about who gets to decide when you’re done. Who holds your hand when you can’t speak? Who says 'no' to the feeding tube? The system’s broken, but the real revolution is in the quiet moments-when a daughter teaches her mom how to swallow again, even if she’ll forget tomorrow. That’s not medicine. That’s love with a plan.

Roshan Joy - 21 January 2026

My uncle had HD. We didn’t have specialists. We had faith, prayer, and a neighbor who drove him to physio every week. He’d laugh when his arms flailed like he was conducting an invisible orchestra. 😊 I’m not saying medicine isn’t important-but don’t forget the people who show up. Even without a plan, love still finds a way.

Adewumi Gbotemi - 22 January 2026

Back home in Nigeria, we don’t have names for these things. We just say 'he is not himself'. But we take care. Whole village helps. Food, bathing, sitting with him at night. No forms. No bills. Just hands. Maybe the real cure is not in labs-but in not letting someone be alone.

Michael Patterson - 23 January 2026

Wow, another feel-good article pretending that 'planning' is a cure. Let me guess-this was written by someone who’s never held a loved one as they choke on their own saliva? You think filling out a living will changes the fact that your brain is rotting from the inside? And 'aquatic therapy'? Like swimming is gonna save someone whose neurons are turning to dust? This isn’t hope. It’s denial with a PowerPoint.

Matthew Miller - 24 January 2026

Let’s cut the crap. You’re not 'choosing how you face it'. You’re being gaslit by a healthcare system that profits from your suffering. Tetrabenazine causes depression? Good. Maybe it helps them feel less of the horror. And 'specialized centers'? They’re luxury condos for dying people with good insurance. The rest of us? We’re left to Google symptoms at 3 AM while our kids wonder why Mom’s laughing at nothing. This isn’t a guide. It’s a sales pitch for a broken system.