What Is CKD-Mineral and Bone Disorder?

When your kidneys start to fail, they don’t just stop filtering waste. They also stop managing the minerals that keep your bones strong and your heart healthy. This is where CKD-MBD - Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder - comes in. It’s not just about weak bones. It’s a whole-body problem involving calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and vitamin D. By Stage 3 of kidney disease, these systems are already starting to go off track. By Stage 5, nearly everyone on dialysis has it.

Doctors used to call this "renal osteodystrophy," but that name only talked about bone damage. We now know the damage goes deeper - into your blood vessels, your heart, and your muscles. In fact, 75 to 90% of dialysis patients show signs of vascular calcification, where calcium builds up in arteries like plaque. That’s why people with advanced kidney disease have up to five times the risk of dying from a heart attack compared to someone without kidney disease.

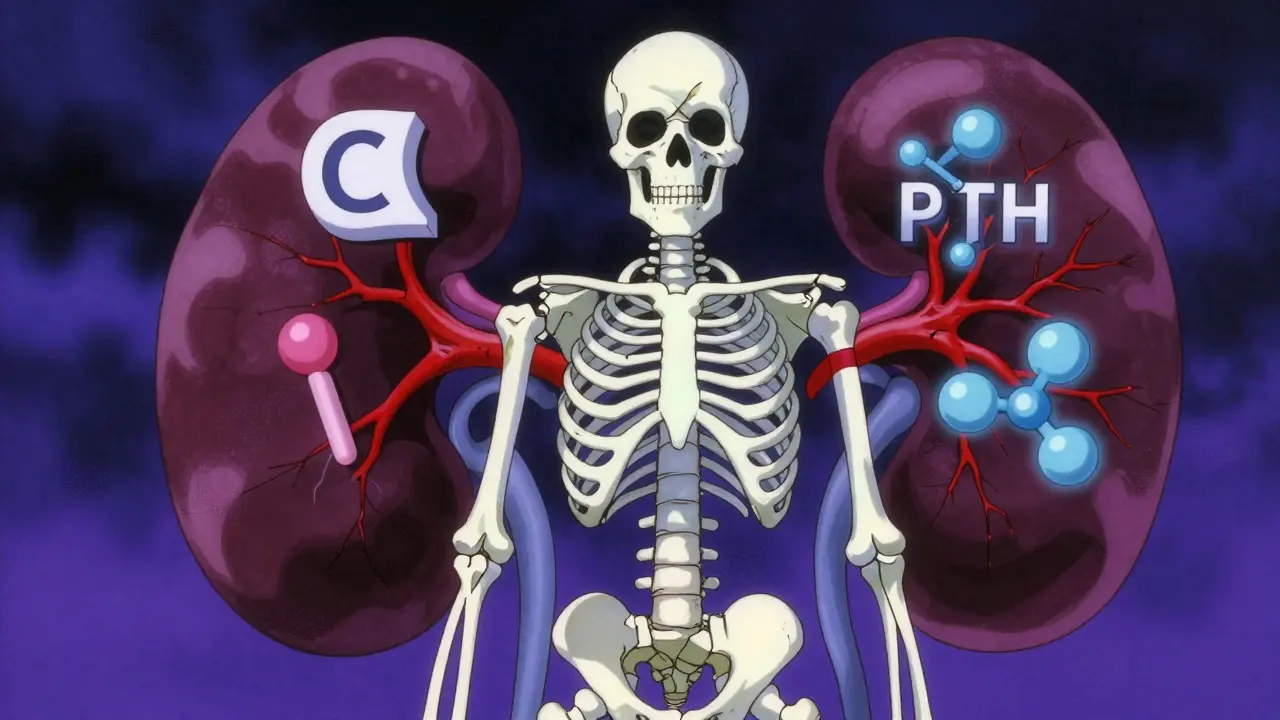

The Three-Part Cycle: Phosphate, PTH, and Vitamin D

Think of CKD-MBD as a broken feedback loop. It starts with phosphate. Healthy kidneys get rid of excess phosphate. But when kidney function drops below 60 mL/min, phosphate starts to pile up. Your body tries to fix this by making more FGF23, a hormone that tells your kidneys to pee out more phosphate. But as kidney damage gets worse, even FGF23 can’t keep up.

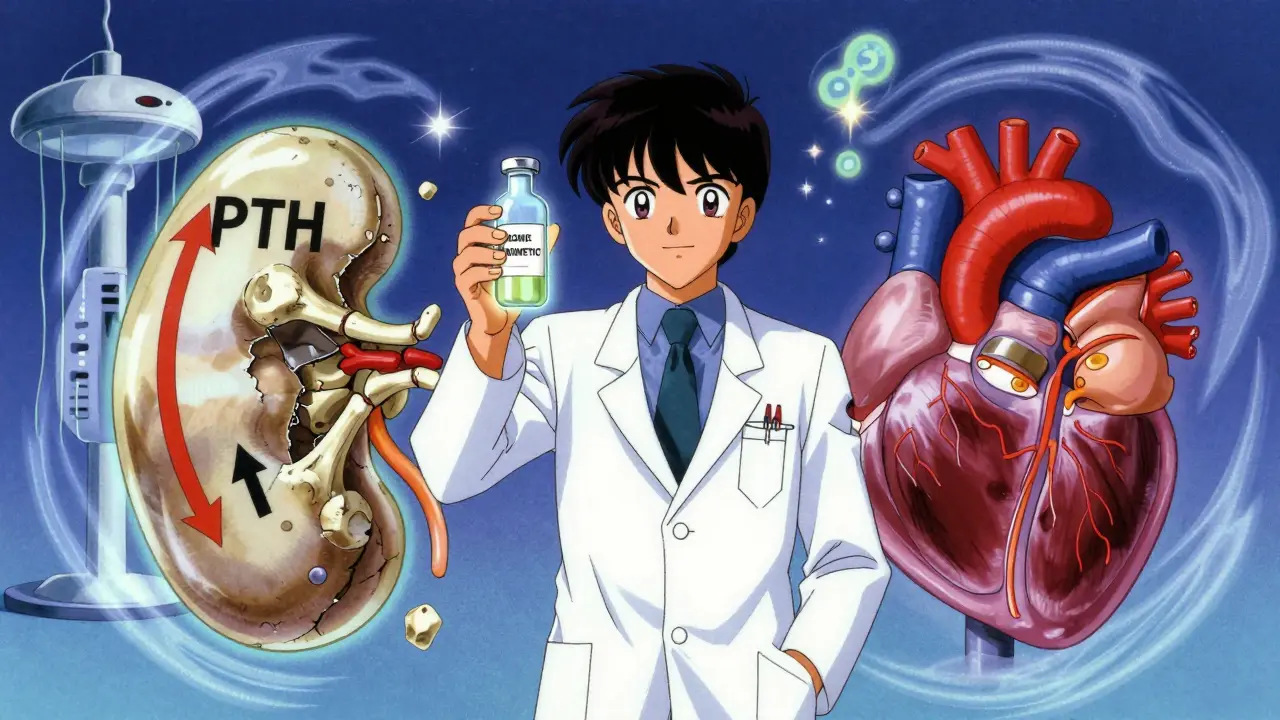

At the same time, your kidneys lose the ability to turn vitamin D into its active form - calcitriol. Without enough calcitriol, your gut can’t absorb calcium properly. Your blood calcium drops. That triggers your parathyroid glands to go into overdrive and pump out more PTH. High PTH pulls calcium out of your bones to keep blood levels stable. That’s why your bones get thin and fragile.

But here’s the twist: even with all that extra PTH, your bones stop responding. This is called "PTH resistance." So you have high PTH, but your bones aren’t being rebuilt. Meanwhile, your blood vessels start soaking up calcium like a sponge. The result? Fractures and heart disease - both happening at the same time.

What the Numbers Mean: Normal vs. CKD Targets

For someone with healthy kidneys, normal calcium is 8.5-10.2 mg/dL, phosphate is 2.5-4.5 mg/dL, and PTH is 10-65 pg/mL. But in CKD, those numbers shift. KDIGO guidelines - the gold standard for kidney care - set different targets:

- Calcium: 8.4-10.2 mg/dL (same as normal, but harder to maintain)

- Phosphate: 2.7-4.6 mg/dL for Stage 3-5; 3.5-5.5 mg/dL for dialysis

- PTH: 2-9 times the upper limit of your lab’s normal range (usually 150-600 pg/mL)

- Vitamin D (25-OH): At least 30 ng/mL - not just "normal," but enough to support bone and immune health

Many patients with Stage 3-5 CKD have vitamin D levels below 20 ng/mL. That’s not just deficiency - it’s a red flag. Studies show these patients have a 30% higher risk of dying than those with levels above 30 ng/mL. And here’s the kicker: supplementing with regular vitamin D (cholecalciferol) lowers death risk by 15%, while active forms like calcitriol don’t - and can even raise calcium and phosphate dangerously.

Bone Disease in CKD: High Turnover, Low Turnover, and Everything In Between

Not all bone problems in CKD look the same. There are three main types:

- High turnover disease (osteitis fibrosa cystica): Caused by very high PTH (over 500 pg/mL). Bones are constantly being broken down and rebuilt, but poorly. You’ll see elevated bone enzymes, and your fracture risk skyrockets.

- Low turnover disease (adynamic bone disease): This is the most common now - affecting 50-60% of dialysis patients. PTH is low (under 150 pg/mL), and bone cells just shut down. Your bone density might look normal on a scan, but your bones are brittle. This is often caused by too much calcium-based binder use or too much active vitamin D.

- Mixed disease: A combination of both, seen in 10-20% of cases.

Here’s what’s surprising: most people think low PTH is good. But in CKD, too-low PTH is just as dangerous as too-high. The goal isn’t to crush PTH - it’s to keep it in a narrow zone where bone can repair itself without overdoing it.

Vascular Calcification: The Silent Killer

One of the scariest parts of CKD-MBD isn’t the bone fractures - it’s what’s happening inside your arteries. Calcium and phosphate don’t just stick to bones. When levels are high, they start depositing in your heart valves, arteries, and even your skin. This isn’t just plaque. It’s actual bone-like tissue forming inside blood vessels.

By Stage 4, 40% of patients already have coronary calcification. By dialysis, that jumps to 80%. Each 1 mg/dL rise in phosphate increases your risk of death by 18%. That’s why doctors now say: "Don’t treat phosphate like a lab number - treat it like a life-or-death signal."

CT scans can detect this early. Plain X-rays miss it about 30-40% of the time. If you’re on dialysis and your doctor hasn’t ordered a heart scan for calcium scoring, ask why.

Treatment: What Actually Works

There’s no magic pill for CKD-MBD. Treatment is about balance - and avoiding the traps.

Phosphate Control

Diet is the first line. Most people need to limit phosphate to 800-1000 mg per day. That means cutting out processed foods, colas, and packaged snacks - they’re loaded with hidden phosphate additives. Whole foods like chicken, fish, and vegetables are safer.

Phosphate binders help, but not all are equal. Calcium-based binders (like calcium carbonate) are cheap, but they can make vascular calcification worse. That’s why many doctors now prefer sevelamer or lanthanum - they don’t add calcium. But they’re more expensive and can cause stomach upset.

Vitamin D: Less Is Often More

Don’t rush to active vitamin D (calcitriol, paricalcitol). These are powerful drugs. Use them only if PTH is above 500 pg/mL and you’re not responding to other treatments. For most people, regular vitamin D (1000-4000 IU daily) is enough to raise 25(OH)D above 30 ng/mL. Studies show this reduces death risk without raising calcium or phosphate.

Calcimimetics: A New Tool

If PTH stays sky-high despite everything else, calcimimetics like cinacalcet or etelcalcetide can help. They trick the parathyroid gland into thinking blood calcium is higher than it is - so it makes less PTH. Etelcalcetide, given as a weekly IV during dialysis, lowers PTH by 45% on average. That’s better than cinacalcet, which only drops it by 30%.

Bone Biopsies: Rare, But Important

Most doctors never do a bone biopsy. But if your PTH is low and you’re breaking bones anyway, or if you’re on long-term dialysis with no clear cause for bone loss, a biopsy can tell you if you have adynamic bone disease. That changes everything - because you need to stop calcium binders and vitamin D, not add more.

What’s New in 2025?

Research is moving fast. Anti-sclerostin antibodies like romosozumab - originally for osteoporosis - are now being tested in CKD patients. Early results show they can increase bone density by 30-40% without worsening calcification. That’s huge.

Another exciting area is Klotho. This protein helps FGF23 work properly. In CKD, Klotho drops by 50-70%. Animal studies show giving Klotho reduces vascular calcification by half. Human trials are coming.

And the biggest shift? We’re now treating CKD-MBD starting in Stage 3 - not waiting until dialysis. Annual vitamin D checks and phosphate monitoring every 6-12 months are now recommended. Why? Because FGF23 starts rising 5-10 years before phosphate does. Catching it early gives you a fighting chance.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you have CKD, here’s your action plan:

- Ask for your serum calcium, phosphate, PTH, and 25(OH) vitamin D levels - and what they mean for you.

- Get a phosphate binder if your levels are high, but avoid calcium-based ones unless your doctor says it’s safe.

- Take regular vitamin D (1000-4000 IU/day) if your level is below 30 ng/mL.

- Ask about a coronary calcium CT scan if you’re on dialysis or have Stage 4-5 CKD.

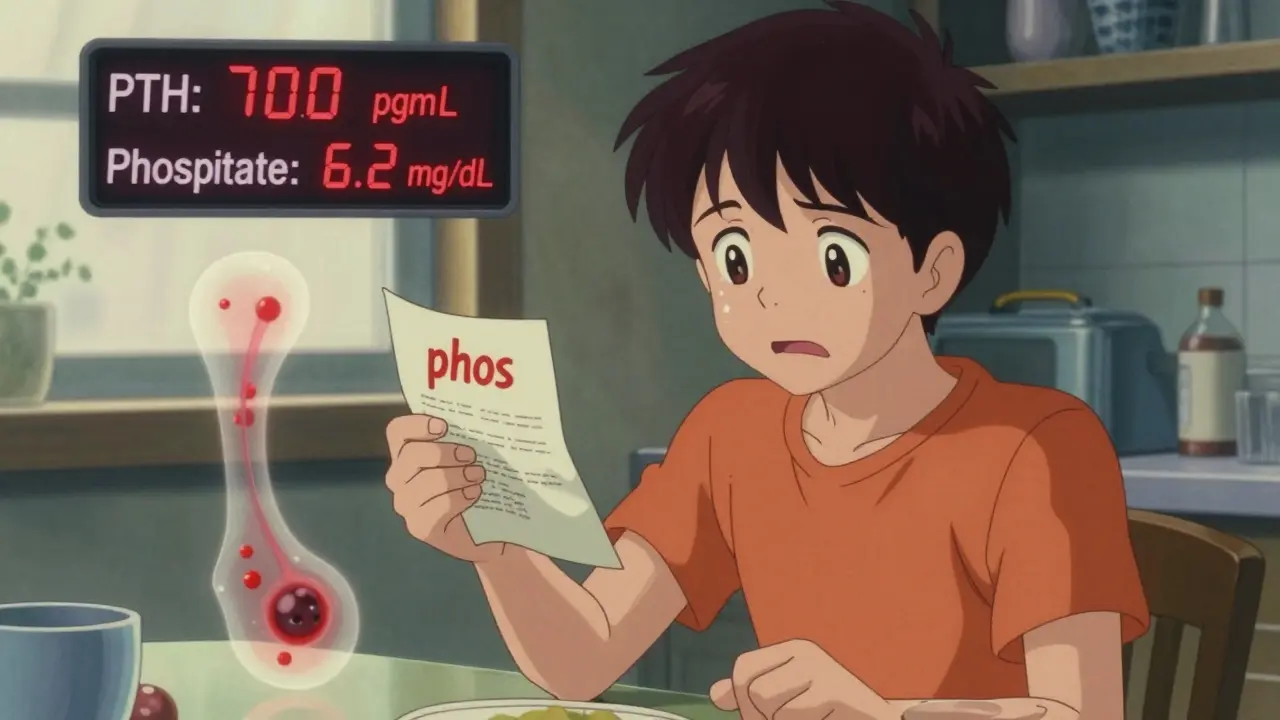

- Read food labels. Avoid anything with "phos" in the ingredients.

- Don’t take active vitamin D unless your PTH is over 500 and your doctor says it’s necessary.

CKD-MBD isn’t something you fix with one pill. It’s a daily balancing act - between food, meds, and monitoring. But if you understand the pieces - calcium, phosphate, PTH, vitamin D - you can work with your team to protect your bones, your heart, and your future.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is high calcium always bad in CKD?

Not always - but it’s dangerous if it’s too high or if it’s paired with high phosphate. The calcium-phosphate product (Ca x P) should stay below 55 mg²/dL². High calcium alone can come from too many calcium-based binders or active vitamin D. That’s why doctors now avoid calcium supplements unless absolutely necessary. The goal is to keep calcium in the normal range, not push it to the top.

Can I get enough vitamin D from sunlight if I have CKD?

Sunlight helps, but your kidneys can’t turn it into the active form. That’s why even people with plenty of sun exposure often have low vitamin D levels in CKD. Supplementing with oral vitamin D3 is the only reliable way to raise your 25(OH)D levels above 30 ng/mL. Sunlight alone won’t cut it.

Why do I need to avoid phosphorus additives in food?

Phosphate additives - like those in processed meats, cheese, colas, and baked goods - are almost 100% absorbed by your gut. Natural phosphate in food (like in chicken or beans) is only 40-60% absorbed. So two cans of soda can give you more phosphate than a whole chicken breast. Avoiding additives is the easiest way to cut phosphate intake without starving yourself.

Does lowering phosphate improve survival?

Yes - but only if done safely. Studies show each 1 mg/dL rise in phosphate increases death risk by 18%. But overly strict limits (below 3.5 mg/dL) can lead to malnutrition and worse outcomes. The sweet spot is 3.5-5.5 mg/dL for dialysis patients. It’s not about being the lowest - it’s about being stable and within target.

Can CKD-MBD be reversed?

Bone damage can improve with proper treatment - especially if caught early. Adynamic bone disease can recover if you stop excess calcium and vitamin D. Vascular calcification is harder to reverse, but slowing it down is possible. One study showed a 15% reduction in calcification progression after 2 years of phosphate control and calcimimetic use. Early, consistent management gives you the best shot.

lokesh prasanth - 19 January 2026

So phosphate is the real villain? Feels like the system is rigged. Kidneys fail, then the body turns on itself. We're just meat with broken math.

MARILYN ONEILL - 21 January 2026

I mean... if you just ate less junk food and took your vitamins like a responsible adult, none of this would happen. People just don't care anymore. It's sad.

Rod Wheatley - 21 January 2026

This is so important! Seriously, folks-this isn't just a kidney thing. It's your heart, your bones, your future. Don't wait until you're on dialysis to care. Start now. Check your numbers. Talk to your doc. Vitamin D isn't optional-it's survival. And please, avoid those sneaky 'phos' additives! Your arteries will thank you. 💪❤️

Jerry Rodrigues - 22 January 2026

Interesting read. I never realized how much bone health ties into heart risk. Makes sense though. Just gotta keep it balanced, right?

Jarrod Flesch - 24 January 2026

I’ve been on dialysis for 4 years and this hits home. 💔 The phosphate binders wreck my stomach but I do ‘em. And yeah, I check labels like a hawk now. No more soda. No more processed cheese. I’d rather eat plain chicken than die early. 🍗🙏

Stephen Rock - 25 January 2026

Of course the pharmaceutical industry loves this. More meds. More binders. More injections. Meanwhile, the real fix-diet and lifestyle-is ignored because it doesn't make money.

Ashok Sakra - 27 January 2026

I had a cousin who died from this. He ignored his labs for years. Now I’m terrified. My dad has CKD. I’m gonna force him to get tested. He thinks he’s fine because he ‘feels okay.’ He’s wrong. So wrong.

Andrew Rinaldi - 29 January 2026

It’s fascinating how nature designed such a delicate balance-and how fragile it becomes when one organ fails. Maybe the body isn’t broken. Maybe it’s just trying to adapt in a world that’s moved too fast.

Gerard Jordan - 29 January 2026

This is gold 🙌. Sharing with my mom who’s in Stage 4. She’s been taking calcium supplements like candy. Gonna make her read this. Also, love the part about Klotho-sounds like sci-fi but it’s real science. 🌱🩺

michelle Brownsea - 31 January 2026

If you're not monitoring your phosphate levels every six months, you're not just being negligent-you're being reckless. And if your doctor hasn't ordered a calcium scan by Stage 4, they're not doing their job. Period.

Malvina Tomja - 1 February 2026

Vitamin D supplements? Please. You think popping a pill fixes everything? You're just masking the problem. Real health is in the soil, in the sun, in the food your grandparents ate. Not in a bottle.

Glenda Marínez Granados - 2 February 2026

So... we’re supposed to believe that active vitamin D is dangerous... but Klotho protein is the next miracle cure? 😏 Meanwhile, I’m just here wondering if we’re all just lab rats in a giant pharmaceutical experiment.