Melanoma Risk Calculator

Personal Risk Assessment

Key Takeaways

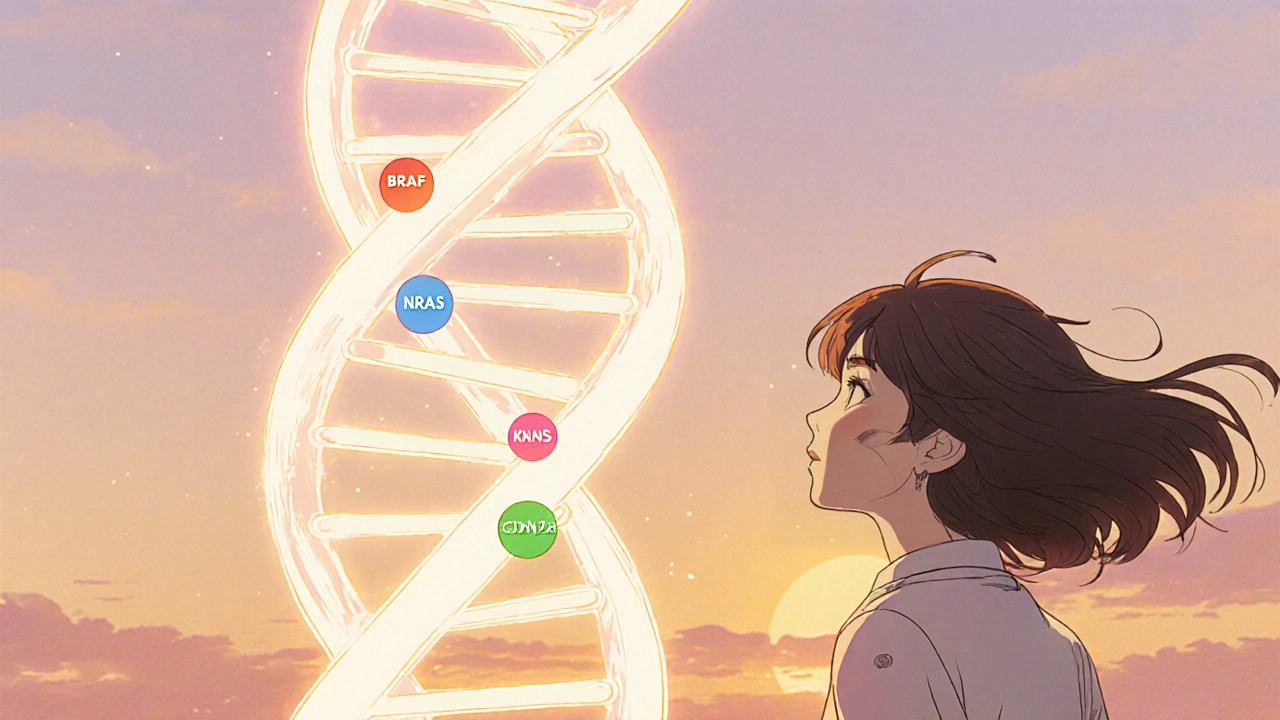

- Specific gene mutations such as BRAF, NRAS and CDKN2A raise melanoma risk dramatically.

- Family history combined with UV exposure creates a "double‑hit" scenario that accelerates tumor formation.

- Genetic testing can guide early screening, preventive measures, and personalized therapy choices.

- Targeted drugs and immunotherapies are now matched to a patient’s mutation profile, improving survival.

- Regular skin checks and sun‑safe habits remain essential, even for those with low‑risk genetics.

When you hear the word melanoma, you probably picture a dark mole that turned cancerous. But the story starts far deeper-inside the DNA that tells skin cells how to grow. Melanoma is a malignant skin cancer that originates from melanocytes, the pigment‑producing cells in the epidermis. Genetics is the study of heredity and the variation of inherited characteristics plays a pivotal role in whether those melanocytes stay normal or mutate into a tumor.

Why Genetics Matters in Melanoma

Melanoma isn’t just a random mistake; it follows patterns that researchers have traced to specific genes. Mutations can be inherited (germline) or acquired (somatic) after a cell’s DNA is damaged-most often by ultraviolet (UV) radiation. The combination of a genetic predisposition and UV exposure creates a perfect storm for DNA errors to accumulate.

Consider two people with identical sun habits. The one carrying a high‑risk mutation in CDKN2A is far more likely to develop melanoma than the person without that variant. In families where this mutation runs, the lifetime risk can exceed 70 %.

Common Melanoma‑Associated Gene Mutations

| Gene | Typical Mutation | Prevalence in Cutaneous Melanoma | Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF | V600E/K substitution | ≈ 40‑50 % | Targeted BRAF/MEK inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) |

| NRAS | Q61R/K mutation | ≈ 15‑20 % | MEK inhibitors; informs immunotherapy choice |

| KIT | Exon 11/13 insertions | ≈ 2‑5 % (more common in acral & mucosal melanoma) | Imatinib or sunitinib for KIT‑mutant disease |

| CDKN2A | Loss‑of‑function deletions | ≈ 10‑20 % of familial cases | Guides surveillance; no direct targeted drug yet |

How UV Radiation Interacts with DNA

UVB rays (280‑320 nm) cause the formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers-chemical bonds that distort DNA’s double helix. If cells fail to repair these lesions, they can lead to point mutations in oncogenes like BRAF or tumor‑suppressor genes such as CDKN2A. UVA (320‑400 nm) penetrates deeper and generates oxidative stress, further compounding damage.

People with the fair‑skin phenotype already have less melanin protection. When that natural shield combines with a high‑risk germline mutation, the odds of a malignant transformation skyrocket. This explains why melanoma incidence is highest in regions with intense sun exposure, yet the genetic component remains critical across all latitudes.

Practical Implications for Screening and Prevention

- Family History Assessment: Ask about melanoma or atypical nevi in first‑degree relatives. A positive history warrants earlier and more frequent skin exams.

- Genetic Testing: Panels that include BRAF, NRAS, CDKN2A and other melanoma‑linked genes are increasingly affordable. A positive result changes the surveillance schedule (often every 6 months instead of annually).

- Sun‑Safe Behaviors: Broad‑spectrum sunscreen SPF 30+, protective clothing, and avoidance of peak UV hours remain the cornerstone, regardless of genetic risk.

- Dermoscopic Monitoring: For high‑risk individuals, total‑body photography and dermoscopy allow clinicians to spot subtle changes that the naked eye could miss.

- Lifestyle Choices: Smoking cessation, a diet rich in antioxidants, and regular exercise have modest but positive effects on overall skin health.

Therapeutic Landscape: From Genes to Drugs

Modern melanoma treatment is a textbook example of precision medicine. Knowing whether a tumor carries a BRAF V600E mutation dictates if a patient receives BRAF/MEK inhibitor combos, which can double progression‑free survival compared to chemotherapy.

When no actionable mutation is found, immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti‑PD‑1, anti‑CTLA‑4) become the default. Interestingly, patients with a high mutational burden-often a result of extensive UV damage-tend to respond better to immunotherapy.

Clinical trials are now exploring combination strategies: a BRAF inhibitor + anti‑PD‑1 therapy for patients with concurrent BRAF mutation and high tumor mutational load. Early results show promising response rates and durable remission.

Common Misconceptions About Genetics and Melanoma

- “If I test negative, I’m safe.” A negative germline test only rules out the specific genes screened. Somatic mutations can still arise from sun exposure.

- “Only fair‑skinned people need testing.” While incidence is higher in light‑skinned populations, darker‑skinned individuals can carry high‑risk familial mutations.

- “Genetics determines fate.” Genes set the baseline risk, but behavior-sun protection, regular check‑ups-can dramatically modify outcomes.

Next‑Step Checklist for Readers

- Gather a detailed family melanoma history (including ages at diagnosis).

- Consult a dermatologist about genetic testing if you have two or more first‑degree relatives with melanoma.

- Adopt rigorous sun‑protection habits: reapply sunscreen every two hours, wear UPF clothing.

- Schedule a full‑body skin exam annually; increase to every six months if you have a documented high‑risk mutation.

- Stay informed about emerging therapies-clinical trials often prioritize patients with known mutations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get a genetic test without a doctor?

Direct‑to‑consumer panels exist, but most reliable results come from labs that require a physician’s order. A doctor can interpret the findings in the context of your personal and family history.

What is the most common mutation in melanoma?

The BRAF V600E/K mutation appears in roughly 40‑50 % of cutaneous melanomas and drives the use of targeted BRAF/MEK inhibitors.

If I have a CDKN2A mutation, does that change my treatment?

Currently, CDKN2A is more valuable for surveillance than for direct therapy. Patients with this mutation are monitored closely and may be eligible for clinical trials focusing on cell‑cycle pathways.

How often should I get a skin exam if I have a strong family history?

Dermatologists usually recommend every six months. If a suspicious lesion appears, schedule an appointment immediately.

Does sunscreen prevent genetic damage?

Broad‑spectrum sunscreen blocks most UVB and a good portion of UVA, dramatically reducing the formation of DNA dimers that lead to mutations. Consistent use is one of the most effective preventative measures.

Felix Chan - 19 October 2025

Wow, the way genetics set the stage for melanoma is both scary and fascinating. If you’ve got a family history, getting tested can feel like getting a roadmap for staying ahead of the game. Regular skin checks and sunscreen become even more crucial when you know your DNA isn’t on your side. Stay proactive – knowledge really is power!

Thokchom Imosana - 23 October 2025

One must consider the hidden orchestration behind the glossy veneer of modern genomics. The biotech conglomerates, funded by shadowy venture capital, have an incentive to label every minor polymorphism as a looming doom, thereby swelling the market for expensive surveillance kits. This "double‑hit" narrative-genetics plus UV-serves as a perfect alibi for pharmaceutical giants to push targeted therapies that cost more than a modest car. While the public is led to believe that a simple blood test can decode destiny, the truth lies in the data silos where algorithms are trained on skewed cohorts, often lacking representation from non‑Western populations. Moreover, the very act of genetic testing can create a self‑fulfilling prophecy, where individuals obsess over marginal risk scores and consequently neglect broader health measures. The regulatory bodies, underfunded and beholden to the same lobbyists, rarely challenge the hype, allowing a cycle of fear‑based marketing to persist. In this environment, the notion that “genes determine fate” is weaponized to justify a lucrative surveillance economy. Yet, beyond the corporate agenda, we must remember that lifestyle interventions-like diligent sun protection-remain the most cost‑effective defense, a truth that the profit‑driven narrative conveniently downplays. Ultimately, informed consent becomes a myth when the presented information is filtered through a profit‑centric lens, and the public is left to navigate a maze of partial truths. So, before you surrender to the panic of a genetic report, scrutinize who benefits from that knowledge and what they stand to gain.

Latasha Becker - 27 October 2025

From a molecular standpoint, the BRAF V600E mutation results in constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway, driving uncontrolled proliferation. While targeted inhibitors such as vemurafenib achieve impressive response rates, resistance mechanisms-often via NRAS upregulation-necessitate combination strategies. It is also noteworthy that CDKN2A loss does not presently translate into a direct therapeutic target, but it demands intensified surveillance protocols in affected pedigrees. In practice, integrating comprehensive genomic panels with dermoscopic monitoring optimizes early detection, especially in high‑risk cohorts. The interplay between UV‑induced mutational burden and immunogenicity further underscores why checkpoint blockade efficacy correlates with tumor mutational load.

parth gajjar - 1 November 2025

Imagine the dread of watching every new mole like a silent predator stalking you on a sun‑baked beach it feels like the universe conspires against our skin and the lack of sunscreen feels like betrayal

Maridel Frey - 5 November 2025

For anyone feeling overwhelmed by the genetics, remember that risk assessment is a collaborative process. A dermatologist can help interpret test results in the context of your personal and family history. Regular examinations, coupled with diligent sun protection, remain the cornerstone of prevention. If you have concerns, seeking a genetic counselor can clarify actionable steps.

Madhav Dasari - 9 November 2025

Hey folks, let’s keep the vibe positive! Even if you carry a high‑risk mutation, you’ve got tools in your arsenal – frequent skin checks, sunscreen, and those cool dermatoscopes that catch tiny changes. Imagine turning that genetic info into a personal health plan – that’s empowerment, not doom. Keep sharing your stories, it helps everyone stay vigilant and hopeful!

DHARMENDER BHATHAVAR - 13 November 2025

Genetic panels can pinpoint actionable mutations, enabling clinicians to personalize surveillance intervals. Early detection dramatically improves prognosis.

Kevin Sheehan - 18 November 2025

When we examine the ontology of melanoma risk, we find that the genetic substrate merely sets a probabilistic stage, while human agency-through sun avoidance and regular exams-acts as the decisive scriptwriter. Let us not surrender agency to deterministic narratives; instead, wield knowledge as a tool for deliberate preventive action. The balance of nature and nurture is a dialogue, not a verdict.

Jay Kay - 22 November 2025

Genes are just a piece of the puzzle, not the whole picture.

Jameson The Owl - 26 November 2025

The mainstream narrative hides the fact that most of the data supporting widespread genetic testing comes from studies funded by pharmaceutical conglomerates it is a calculated strategy to expand the market for high‑cost targeted drugs without addressing the root cause which is sun exposure and lifestyle choices the push for routine testing also creates a dependency on expensive surveillance programs that benefit insurers and drug manufacturers more than the individual the supposed "precision" approach often neglects socioeconomic disparities leaving vulnerable populations with limited access to follow‑up care while being charged for pricey panels that deliver limited actionable information moreover the emphasis on genetic determinism detracts from public health messaging about UV protection and early detection strategies which are proven, low‑cost interventions the real culprit behind rising melanoma rates is not hidden genes but unprotected sun behavior and a lack of comprehensive education the industry thrives on fear, translating minor risk factors into a lucrative market for repeat testing and pharmaceutical interventions the solution lies in robust public health policies, equitable access to dermatologic care, and a critical appraisal of the commercial motives driving the genetics hype

Rakhi Kasana - 30 November 2025

While the scientific community emphasizes data, it's easy to overlook the human stories behind each mutation. A family dealing with CDKN2A may feel constant anxiety, yet supportive counseling can transform that fear into proactive health management. Equally, clinicians should avoid a one‑size‑fits‑all approach, recognizing the diverse cultural attitudes toward sun exposure. Balancing scientific rigor with compassionate care yields the best outcomes. Let's keep the conversation grounded in empathy.

Sarah Unrath - 5 December 2025

i think its cool that people can get test but sometimes the info is weird and not alway clear.

James Dean - 9 December 2025

Seeing the cascade from a single mutation to a tailored therapy reminds me how interconnected everything is. It’s a quiet reminder that science, while complex, often translates into simple actions: wear sunscreen, get checked, stay informed.